10 most common mistakes using terraform

We had the chance to see quite a bit of infrastructures in our years of experience with AWS, GCP and Azure and we see some mistakes being repeated. No shame in that, we’ve done most of these too!

I’ll try to show the ones we see very often and talk a bit about how to fix them.

BTW we did a blogpost about “10 most common mistakes using kubernetes”

1. using local state

Terraform state is stored by default in a local file named terraform.tfstate, but it can also be stored remotely, which works better in a team environment.

Terraform uses this local state to create plans and make changes to your infrastructure. Prior to any operation, Terraform does a refresh to update the state with the real infrastructure.

When working with Terraform in a team, use of a local file makes Terraform usage complicated since each user must make sure they always have the latest state data before running Terraform and make sure that nobody else runs Terraform at the same time.

With remote state, Terraform writes the state data to a remote data store, which can then be shared between all members of a team. Terraform supports storing state in Terraform Cloud, HashiCorp Consul, Amazon S3, Azure Blob Storage, Google Cloud Storage, Alibaba Cloud OSS, and more.

Remote state is a feature of backends. Configuring and using remote backends is easy and you can get started with remote state quickly. If you then want to migrate back to using local state, backends make that easy as well.

An example of a remote backend in S3 with explicit DynamoDB locking:

terraform {

backend "s3" {

bucket = "my-terraform-tfstate"

key = "prod"

region = "us-east-1"

dynamodb_table = "terraform_locks"

encrypt = true

}

}

Super easy, no? Don’t commit your terraform.tfstate to your git repo and use your vendor’s object storage.

2. secrets in plaintext

Do you have secrets in terraform.tfvars or anywhere else in your *.tfvars? Or even in the *.tf files themselves? Are they commited to your repo?

Are you aware that terraform.tfstate might contain some secrets too? (See the previous tip why to use remote backend anyway).

First, make sure to use a good .gitignore for terraform projects.

Second, make sure there are no plaintext sensitive values in any of your unencrypted files.

But how do you do that? You can choose from two approaches:

- encrypt the secrets and version them along with the configuration

- store the secrets externally and pull them only when needed

encrypted secrets in version control

We usually advocate for the first approach as it is easier to use something like mozilla/sops CLI tool to encrypt and decrypt yaml/json values. Using sops is super awesome because it:

- integrates with managed cloud KMS (Key Management Service to manage your cryptography keys and delegate access to them and rotate/revoke them when needed)

- encrypts only json/yaml values, NOT keys and that makes Code Review so much smoother!

- is supported by

terragrunt - keeps your secrets versioned too in the same codebase and makes it easier to handle change management

Unfortunately sops still does not support HCL but there are some ways around this.

an example of encrypted yaml:

myapp1: ENC[AES256_GCM,data:Tr7o=,iv:1=,aad:No=,tag:k=]

app2:

db:

user: ENC[AES256_GCM,data:CwE4O1s=,iv:2k=,aad:o=,tag:w==]

password: ENC[AES256_GCM,data:p673w==,iv:YY=,aad:UQ=,tag:A=]

# private key for secret operations in app2

key: |-

ENC[AES256_GCM,data:Ea3kL5O5U8=,iv:DM=,aad:FKA=,tag:EA==]

an_array:

- ENC[AES256_GCM,data:v8jQ=,iv:HBE=,aad:21c=,tag:gA==]

- ENC[AES256_GCM,data:X10=,iv:o8=,aad:CQ=,tag:Hw==]

- ENC[AES256_GCM,data:KN=,iv:160=,aad:fI4=,tag:tNw==]

sops:

kms:

# ... redacted for brevity ...

external secrets management

The second approach where you use some external system (like GitHub Secrets, GitLab CI/CD environment variables, HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, etc.) to manage your secrets is a bit more:

- complex - pulling secrets (with auth) in pipeline and local dev

- pricy - for the external solution costs

and has the disadvantage of not having the secrets versioned along with the others assets.

But this approach definitely has its place too, especially in bigger corporations!

And anything is better really than having your sensitive values in plaintext somewhere!

3. terraform binary version mismatch

Have you ever seen this annoying error?

Error: state snapshot was created by Terraform v0.12.29,

which is newer than current v0.12.20; upgrade to

Terraform v0.12.29 or greater to work with this state

You might have a version pinned in your pipeline and the same version on your local machine. Somebody from the team upgrades their terraform binary to the newest version and applies locally - now the pipeline is broken and everybody else from the team has to upgrade to the newest version as well.

Version Constraints

Sometimes when working with an older state and hcl configs and using the newest binary you’ll run in super weird errors – not like the one above that clearly states the problem – due to the lack of backward compatibility and you’ll spend a lot of time debugging a simple binary version mistmach.

Oh, and working on multiple codebases with different terraform versions? Nightmare.

Make sure to set Version Constraints:

terraform {

required_version = "~> 0.12.29"

}

to let the users know that this codebase/module should be used with terraform >= 0.12.29 but < 0.13 like in this case, or use other operators to enforce some other Version Constraints.

and get a nicer error like this one:

Error: Unsupported Terraform Core version

on providers.tf line 20, in terraform:

20: required_version = "~> 0.12.29"

This configuration does not support Terraform version 0.12.28. To proceed,

either choose another supported Terraform version or update this version

constraint. Version constraints are normally set for good reason, so updating

the constraint may lead to other errors or unexpected behavior.

This is going to work only with things like terraform validate but not with terraform plan.

tfenv

To better manage terraform binaries locally I’d recommend a great little tool tfenv which makes it super easy to install old and new terraform versions and switch between them.

$ tfenv install 0.12.28

Installing Terraform v0.12.28

Downloading release tarball from https://releases.hashicorp.com/terraform/0.12.28/terraform_0.12.28_darwin_amd64.zip

##################################################################################################################################################################### 100.0%

Downloading SHA hash file from https://releases.hashicorp.com/terraform/0.12.28/terraform_0.12.28_SHA256SUMS

Unable to verify OpenPGP signature unless logged into keybase and following hashicorp

Archive: tfenv_download.s80lUU/terraform_0.12.28_darwin_amd64.zip

inflating: /usr/local/Cellar/tfenv/2.0.0/versions/0.12.28/terraform

Installation of terraform v0.12.28 successful. To make this your default version, run 'tfenv use 0.12.28'

$ tfenv use 0.12.28

Switching default version to v0.12.28

Switching completed

$ tfenv list

0.13.4

0.12.29

* 0.12.28 (set by /usr/local/Cellar/tfenv/2.0.0/version)

0.11.9

Done!

4. not pinning modules and providers versions

Similar issue to the previous one is not pinning versions of modules and providers.

Save yourselves some headaches when solving mismatches between different local and remote versions of an unpinned external terraform module and providers. Same as using :latest image tag with docker - you are playing with fire.

Pin each version in the terraform configuration and make the upgrades explicit and visible in the versioned code to better handle the process of upgrades.

module "vpc" {

source = "terraform-aws-modules/vpc/aws"

version = "2.47.0"

# all the other things

}

terraform {

required_version = ">= 0.12.9, != 0.13.0"

required_providers {

aws = ">= 2.55.0"

local = ">= 1.4"

null = ">= 2.1"

template = ">= 2.1"

random = ">= 2.1"

kubernetes = ">= 1.11.1"

}

}

5. missing docs

Please document your stuff.

Terraform’s HCL makes it easy to add comments alongside your configuration:

# When this issue https://github.com/hashicorp/terraform/issues/xxxx gets resolved

# we can define our blabla in a more bleble way

escalation_message = lookup(each.value, "escalation_message", null)

it also makes it easy to document your variables (parameters of your infrastructure) and outputs:

variable "cloudsql_disk_size_gb" {

type = number

default = 256

description = "Size of the Cloud SQL disk, in GB."

}

output "cluster_certificate_authority_data" {

description = "Nested attribute containing certificate-authority-data for your cluster. This is the base64 encoded certificate data required to communicate with your cluster."

value = element(concat(aws_eks_cluster.this[*].certificate_authority[0].data, list("")), 0)

}

Then using something like terraform-docs you can generate simple docs in markdown!

terraform-docs markdown . > README.md

Now your terraform codebase is much better documented and easier for onboarding in it. And it was super simple to do it!

6. not running terraform fmt

The terraform fmt command is used to rewrite Terraform configuration files to a canonical format and style. This command applies a subset of the Terraform language style conventions, along with other minor adjustments for readability.

Run this command (ideally in a pre-commit hook) so that all the added/changed terraform configuration is always formatted correctly before it gets versioned in git (afterwards its harder to use things like git blame if there is somebody else formatting the code for you all the time).

it could look something like this (credit to Anton Babenko):

repos:

- repo: git://github.com/antonbabenko/pre-commit-terraform

rev: v1.43.0

hooks:

- id: terraform_fmt

- id: terraform_docs

then just go ahead and every time you git commit a change in any terraform file, it will get automatically formatted (forces you to re-add and commit again) and generates the docs for you.

You might want to use pre-commit hooks for linting yaml, json, bash and all the other stuff that typically come with terraform codebases.

7. non-modular modules

Terraform does not support a folder layout to structure your project, meaning: you can’t use simply organize your *.tf files in subfolders in one shared terraform state.

For this reason some people just go ahead and create modules that are not:

- modular

- reusable

- readable

- doing one thing

- easily changed

an example usually goes like this:

module "dns" {

source = "./dns"

dns_zones = var.dns_zones

dns_records = merge(

var.dns_records,

{

# some other stuff

},

)

}

with all the zones and records resources dumped into the module folder.

Then somebody comes in with request for a new environment and you just create an instance of this module in, having to rewrite half of the module to support a new environment but also be compatible with the old one. Things become even less readable.

Cost of change rapidly increases.

Then the infrastructure complexity grows – so much more you have to split the terraform state (or the whole codebase) in two. Then you have to split the dns module in two as well. Welcome to hell.

Be very careful about using modules in this non-modular and not-reusable way and make sure nobody tries to reuse that module somewhere else in the codebase to avoid future refactoring.

8. not using module registry

Are you writing your own modules for everything?

There’s a great terraform registry with all open-sourced community modules. Chances are they already support everything you need and if not - submit a github issue or a PR with the desired functionality!

There is no need to write everything yourself and maintain it unless you really need it!

If your module is unique or better than an existing one, make sure to give back to the OSS community! :)

9. too big / too small terraform state

You can come to a point when the terraform state is too big - meaning refreshing it takes a lot of time or the blast radius is too big (deleting by mistake a small part of a system vs. deleting everything).

What do you do? You split the terraform state in “half”. Hopefully you split it considering some org/service boundaries and not per resource-type (see tip #10).

But don’t get crazy about splitting everything in smaller and smaller states! With more and more states you need more complexity and support of tooling for all the plan & apply pipeline stages and resolving dependencies between states.

With one state terraform takes cares of computing all dependencies (in which order to create resources) and applying changes in order as one transaction and not much can go wrong (except for the mighty terraform destroy). Switching from one state to multiple, you have to ensure all of it yourselves.

Splitting the state simply comes with its trade-offs.

10. bad directory structure / non-org structure

I see very often that people tend to organize terraform codebases based of the resource-type rather than org or service-level boundaries. E.g.

resource-type layout:

terraform

├── cloudfront

│ └── main.tf

├── dns

│ └── main.tf

├── eks

│ └── main.tf

└── iam

└── main.tf

vs.

service-level layout:

terraform

├── client

│ └── main.tf

├── generator

│ └── main.tf

└── recommender

└── main.tf

The resource-type (first exhibit) makes little sense as it allows the “non-modular” modules (see tip #7) anti-pattern to happen and it will create a lot of issues down the road when the infrastructure or organization grows and terraform state or codebase needs to be split to pass on the ownership to more people & teams.

The service-level layout much better isolates dependencies between its resources inside of a single terraform state.

Organize the terraform configuration in a manner that better copies the corporate structure (teams & services) to avoid huge future refactoring.

bonus: going crazy with for-each, modules, dynamic blocks to fight little boilerplate!

If you write widely-used modules you end up using quite complex configuration using advanced terraform features like conditional creation with count or for-each, dynamic blocks and built-in functions for data transformation.

All these things make the configuration hard to read and change. But if you essentially do that so the users of your modules can easily provision a complex infrastructure with a simple API (the variables of your module), it is reasonable to push the complexity to your module so that the end users have a nice simple module instantiation and great UX.

Consider this example:

module "elb_http" {

source = "terraform-aws-modules/alb/aws"

version = "~> 5.0"

load_balancer_type = "network"

internal = false

name = "nlb-example"

vpc_id = module.vpc.vpc_id

subnets = slice(module.vpc.public_subnets, 0, 2)

http_tcp_listeners = [

{

port = 80

protocol = "TCP"

target_group_index = 0

},

{

port = 443

protocol = "TCP"

target_group_index = 1

},

]

target_groups = [

{

name_prefix = "nginx-"

backend_protocol = "TCP"

backend_port = 32080

target_type = "instance"

deregistration_delay = 10

proxy_protocol_v2 = true

health_check = {

enabled = true

interval = 30

path = "/healthz"

port = "traffic-port"

healthy_threshold = 3

unhealthy_threshold = 3

timeout = 6

protocol = "HTTP"

}

stickiness = {

enabled = false

type = "lb_cookie"

}

},

{

name_prefix = "nginx-"

backend_protocol = "TCP"

backend_port = 32443

target_type = "instance"

proxy_protocol_v2 = true

health_check = {

enabled = true

interval = 30

path = "/healthz"

port = "traffic-port"

healthy_threshold = 3

unhealthy_threshold = 3

timeout = 10

protocol = "HTTPS"

}

stickiness = {

enabled = false

type = "lb_cookie"

}

},

]

}

}

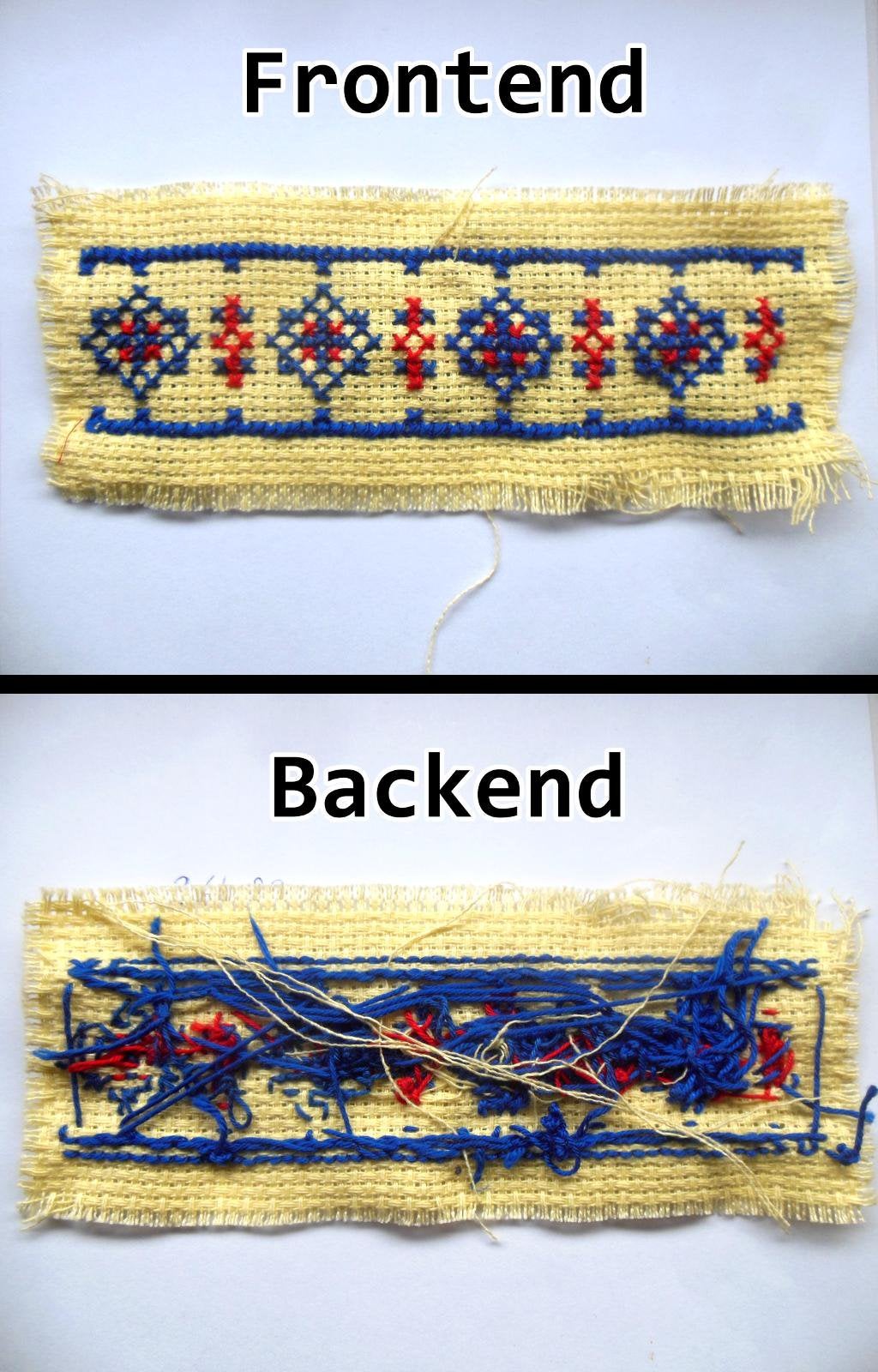

Isn’t it neat to just think about a loadbalancer as a config of its frontend & backend ports and protocol and the routing between them, its healthchecks and some other basic configuration, having some best practices enforced inside of the module itself?

this is a very small example of how the actual implementation looks like:

...

resource "aws_lb_target_group" "main" {

count = var.create_lb ? length(var.target_groups) : 0

name = lookup(var.target_groups[count.index], "name", null)

protocol = lookup(var.target_groups[count.index], "backend_protocol", null) != null ? upper(lookup(var.target_groups[count.index], "backend_protocol")) : null

...

dynamic "health_check" {

for_each = length(keys(lookup(var.target_groups[count.index], "health_check", {}))) == 0 ? [] : [lookup(var.target_groups[count.index], "health_check", {})]

...

}

...

# Host header condition

dynamic "condition" {

for_each = [

for condition_rule in var.https_listener_rules[count.index].conditions :

condition_rule

if length(lookup(condition_rule, "host_headers", [])) > 0

]

Looks a bit scary, no?

This is a great abstraction because it has to look pretty and simple on the front and it is fine that the underlying layer is very scary. But still this thing allows to configure about everything you’ll ever need!

What is the problem then?

Well the problem is when you are not writing a widely-used module or not writing a module at all and leak all of these horrible-to-read advanced terraform features in the root configuration just because you wanted to find out how for-each works or you wanted to get rid of that one extra boilerplate line of config so you built this horrible monster.

Keep your “code” DRY, but not at the expense of simplicity. There is nothing wrong about a bit of boilerplate and clean flat configuration that is easy to read and change!

summary

Infrastructure as Code and terraform are fairly new. There is still a lot to be done to find out best practices, improve linting, testing and collaboration on terraform codebases. It is easy to mess up and create a lot of complexity that is hard to change. Don’t expect that everything will work automagically. Play with it, experiment, seek to constantly learn more about it and collaborate with the OSS community.

Do you see different mistakes being made? Just hit us up (@MarekBartik @MstrsObserver) on Twitter!