10 most common mistakes using kubernetes

We had the chance to see quite a bit of clusters in our years of experience with kubernetes (both managed and unmanaged - on GCP, AWS and Azure), and we see some mistakes being repeated. No shame in that, we’ve done most of these too!

I’ll try to show the ones we see very often and talk a bit about how to fix them.

resources - requests and limits

This definitely deserves the most attention and first place in this list.

CPU request are usually either not set or set very low (so that we can fit a lot of pods on each node) and nodes are thus overcommited. In time of high demand the CPUs of the node are fully utilized and our workload is getting only “what it had requested” and gets CPU throttled, causing increased application latency, timeouts, etc.

BestEffort (please don’t):

resources: {}

very low cpu (please don’t):

resources:

requests:

cpu: "1m"

On the other hand, having a CPU limit can unnecessarily throttle pods even if the node’s CPU is not fully utilized which again can cause increased latency. There is a an open discussion around CPU CFS quota in linux kernel and cpu throttling based on set cpu limits and turning off the CFS quota. CPU limits can cause more problems than they solve. See more in the link below.

Memory overcommiting can get you in more trouble. Reaching a CPU limit results in throttling, reaching memory limit will get your pod killed. Ever seen OOMkill? Yep, that’s the one we are talking about. Want to minimize how often it can happen? Don’t overcommit your memory and use Guaranteed QoS (Quality of Service) setting memory request equal to limit like in the example below. Read more about the topic in Henning Jacobs' (Zalando) presentation.

Burstable (more likely to get OOMkilled more often):

resources:

requests:

memory: "128Mi"

cpu: "500m"

limits:

memory: "256Mi"

cpu: 2

Guaranteed:

resources:

requests:

memory: "128Mi"

cpu: 2

limits:

memory: "128Mi"

cpu: 2

So what can help you when setting resources?

You can see the current cpu and memory usage of pods (and containers in them) using metrics-server. Chances are, you are already running it. Simply run these:

kubectl top pods

kubectl top pods --containers

kubectl top nodes

However these show just the current usage. That is great to get the rough idea about the numbers but you end up wanting to see these usage metrics in time (to answer questions like: what was the cpu usage in peak, yesterday morning, etc.). For that, you can use Prometheus, DataDog and many others. They just ingest the metrics from metrics-server and store them, then you can query & graph them.

VerticalPodAutoscaler can help you automate away this manual process - looking at cpu/mem usage in time and setting new requests and limits based on that all over again.

Utilizing effectively your compute is not an easy task. It is like playing tetris all the time. If you find yourself paying a lot for compute while having low average utilization (say ~10%), you might want to check AWS Fargate or Virtual Kubelet based products that leverage more of a serverless/pay-per-usage billing model that might be cheaper for you.

liveness and readiness probes

By default there are no liveness and readiness probes specified. And sometimes it stays that way…

But how else would your service get restarted when there is an unrecoverable error? How does a loadbalancer know a specific pod can start handling traffic? Or handle more traffic?

People usually don’t know the difference between these two.

- Liveness probe restarts your pod if the probe fails

- Readiness probe disconnects on fail the failing pod from the kubernetes service (you can check this in

kubectl get endpoints) and no more traffic is being sent to it until the probe succeeds again

and BOTH RUN DURING THE WHOLE POD LIFECYCLE. This is important.

People often think that readiness probes run only at the start to tell when the pod is Ready and can start servicing traffic. But that’s just one of its use cases.

The other one is to tell if during a pod’s life the pod becomes too hot handling too much traffic (or an expensive computation) so that we don’t send her more work to do and let her cool down, then the readiness probe succeeds and we start sending in more traffic again. In this case (when failing readiness probe) failing also liveness probe would be very counterproductive. Why would you restart a pod that is healthy and doing a lot of work?

Sometimes not having either probe defined is better than having them defined wrong. As mentioned above, if liveness probe is equal to readiness probe, you are in a big trouble. You might want to start with defining only the readiness probe alone as liveness probes are dangerous.

Do not fail either of the probes if any of your shared dependencies is down, it would cause cascading failure of all the pods. You are shooting yourself in the foot.

LoadBalancer for every http service

Chances are you have more http services in your cluster which you’d like to expose to the outside world.

If you expose kubernetes service as a type: LoadBalancer, its controller (vendor specific) will provision and reconciliate an external LoadBalancer (not necessarily L7 loadbalancer, more likely an L4 lb) and those resources might get expensive (external static ipv4 address, compute, per-second pricing…) as you create many of them.

In that case, sharing one external loadbalancer might make more sense and you expose your services as type: NodePort. Or yet better, deploying something like nginx-ingress-controller (or traefik) being the single NodePort endpoint exposed to the external loadbalancer and routing the traffic in the cluster based on kubernetes ingress resources.

The other in-cluster (micro)services that talk to each other can talk through ClusterIP services and out-of-box dns service discovery. Be careful about not using their public DNS/IPs as it could affect their latency and cloud cost.

non-kubernetes-aware cluster autoscaling

When adding and removing nodes to/from the cluster, you shouldn’t consider some simple metrics like a cpu utilization of those nodes. When scheduling pods, you decide based on a lot of scheduling constraints like pod & node affinities, taints and tolerations, resource requests, QoS, etc. Having an external autoscaler that does not understand these constraints might be troublesome.

Imagine there is a new pod to be scheduled but all of the CPU available is requested and pod is stuck in Pending state. External autoscaler sees the average CPU currently used (not requested) and won’t scale out (will not add another node). The pod won’t be scheduled.

Scaling-in (removing a node from the cluster) is always harder. Imagine you have a stateful pod (with persistent volume attached) and as persistent volumes are usually resources that belong to a specific availability zone and are not replicated in the region, your custom autoscaler removes a node with this pod on it and scheduler cannot schedule it onto a different node as it is very limited by the only availability zone with your persistent disk in it. Pod is again stuck in Pending state.

The community is widely using cluster-autoscaler which runs in your cluster and is integrated with most major public cloud vendors APIs, understands all these constraints and would scale-out in the mentioned cases. It will also figure out if it can gracefully scale-in without affecting any constraints we have set and saves you money on compute.

Not using the power of IAM/RBAC

Don’t use IAM Users with permanent secrets for machines and applications rather than generating temporary ones using roles and service accounts.

We see it often - hardcoding access and secret keys in application configuration, never rotating the secrets when you have Cloud IAM at hand. Use IAM Roles and service accounts instead of users where suitable.

Skip kube2iam, go directly with IAM Roles for Service Accounts as described in this blogpost by Štěpán Vraný.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

annotations:

eks.amazonaws.com/role-arn: arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/my-app-role

name: my-serviceaccount

namespace: default

One annotation. That wasn’t that hard, no?

Also don’t give the service accounts or instance profiles admin and cluster-admin permissions when they don’t need it. That is a bit harder, especially in k8s RBAC, but still worth the effort.

self anti-affinities for pods

Running e.g. 3 pod replicas of some deployment, node goes down and all the replicas with it. Huh? All the replicas were running on one node? Wasn’t Kubernetes supposed to be magical and provide HA?!

You can’t expect kubernetes scheduler to enforce anti-affinites for your pods. You have to define them explicitly.

// omitted for brevity

labels:

app: zk

// omitted for brevity

affinity:

podAntiAffinity:

requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- labelSelector:

matchExpressions:

- key: "app"

operator: In

values:

- zk

topologyKey: "kubernetes.io/hostname"

That’s it. This will make sure the pods will be scheduled to different nodes (this is being checked only at scheduling time, not at execution time, hence the requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution).

We are talking about podAntiAffinity on different node names - topologyKey: "kubernetes.io/hostname" - not different availability zones. If you really need proper HA, dig a bit deeper in this topic.

no poddisruptionbudget

You run production workload on kubernetes. Your nodes & cluster have to be upgraded, or decommissioned, from time to time. PodDisruptionBudget (pdb) is sort of an API for service guarantees between cluster-administrators and cluster-users.

Make sure to create pdb to avoid unnecessary service outages due to draining nodes.

apiVersion: policy/v1beta1

kind: PodDisruptionBudget

metadata:

name: zk-pdb

spec:

minAvailable: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: zookeeper

With this as a cluster-user you tell the cluster-administrators: “hey, I have this zookeeper service here and no matter what you have to do, I’d like having at least 2 replicas always available”.

I talked about this topic more in-depth here in this blogpost.

more tenants or envs in shared cluster

Kubernetes namespaces don’t provide any strong isolation.

People seem to expect if they separated non-prod workload to one namespace and prod to prod namespace, one workload won’t ever affect the other. It is possible to achieve some level of fairness - resource requests and limits, quotas, priorityClasses - and isolation - affinities, tolerations, taints (or nodeselectors) - to “physically” separate the workload in data plane but that separation is quite complex.

If you need to have both types of workloads in the same cluster, you’ll have to bear the complexity. If you don’t need it and having another cluster is relatively cheap for you (like in public cloud), put it in different cluster to achieve much stronger level of isolation.

externalTrafficPolicy: Cluster

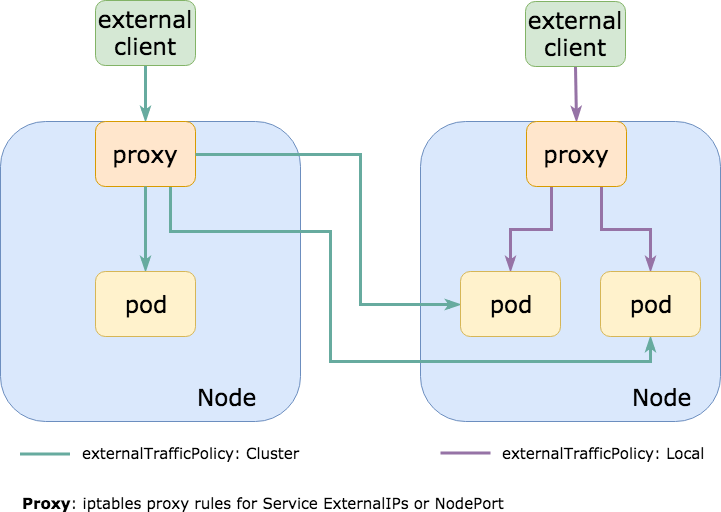

Seeing this very often, all traffic is routed inside the cluster to a NodePort service which has, by default, externalTrafficPolicy: Cluster. That means the NodePort is opened on every node in the cluster so that you can use any of them to communicate with the desired service (set of pods).

More often than not the actual pods that are targeted with the NodePort service run only on a subset of those nodes. That means if I talk to a node which does not have the pod running it will forward the traffic to a different node, causing additional network hop and increased latency (if the nodes are in different AZs/datacenters, the latency can be quite high and there is additional egress cost to it).

Setting externalTrafficPolicy: Local on the kubernetes service won’t open that NodePort on every Node, but only on the nodes where the pods are actually running. If you use an external loadbalancer which is healthchecking its endpoints (like AWS ELB does) it will start to send the traffic only to those nodes where it is supposed to go, improving your latency, compute overhead, egress bill and sanity.

Chances are, you have something like traefik or nginx-ingress-controller being exposed as NodePort (or LoadBalancer, which uses NodePort too) to handle your ingress http traffic routing and this setting can greatly reduce the latency on such requests.

great blogpost that goes more in depth about externalTrafficPolicy and their trade-offs here.

pet clusters + stressing the control plane too much

You went from calling your servers Anton, HAL9000 and Colossus to having generated random ids for your nodes but you started to call your cluster by a name?

You know how you started with a Proof Of Concept with Kubernetes, named the cluster “testing” and STILL use it in production and everybody is scared to touch it? (true story)

Pet clusters are not fun and you might want to consider deleting your cluster from time to time, practice Disaster Recovery and take care of your control plane. Being afraid of touching the control plane is not a good sign. Etcd’s dead? Well, you got a big problem.

On the other hand, touching it too much is no good either. When with time the control plane becomes slow, chances are, you are either creating a lot of objects without ever rotating them (very common when using helm with default settings which does not rotate its state in configmaps/secrets and you end up having thousands of objects in control plane) or you constantly scrape and edit tons of things from kube-api (for autoscaling, cicd, monitoring, logs from events, controllers, etc.).

Also, check your managed kubernetes offering “SLAs”/SLOs and guarantees. A vendor might guarantee availability of control plane (or its subcomponents) but not p99 latency of the requests you send to it. In other words, you might do kubectl get nodes and get correct answer in 10 minutes and that still does not violate the service guarantee.

bonus: using latest tag

This one is a classic. I feel like lately I don’t see this very often as a lot of us got burned too many times and we stopped using :latest and started to pin the versions. Yay!

ECR has a great feature of tag immutability, definitely worth checking out.

summary

Don’t expect that everything works automagically - Kubernetes is not a silver bullet. A bad app will be bad app even on kubernetes (possible even worse than bad, actually). If you are not careful, you can end up with a lot of complexity, stressed and slow control plane and no DR strategy. Don’t expect out-of-box multi-tenancy and high availability. Invest some time in making your app cloud native.

Check how we others got burned in this great failure stories compilation by Henning.

Do you see different mistakes being made? Just hit us up (@MarekBartik @MstrsObserver) on Twitter!